From the Head's Study - Reading is a courageous act

Recently, I’ve been reflecting on how often I manage to pick up a book. Sadly, not too often at the moment, and I feel the difference. Don’t get me wrong, I read a lot of things, but they tend to be articles, policies, thought pieces, emails… not the “lose yourself in the moment” of a good novel. I wonder how many of us find the same.

It is something that feels increasingly urgent in today’s world: the importance of reading not just for academic success, but for the human experience. In a world where notifications compete for our attention and algorithms curate our every click, the quiet, sustained act of reading can feel almost radical. Yet it remains one of the most powerful tools we have.

We live in an era of constant distraction. The average teenager spends over seven hours a day on screens, according to Ofcom’s latest report. That’s more time than they spend sleeping. And while technology brings undeniable benefits, it also fragments attention and reduces opportunities for deep thinking. Reading, by contrast, demands focus. It teaches patience. It cultivates imagination. It is, in many ways, the antidote to the dopamine-driven scroll.

We live in an era of constant distraction. The average teenager spends over seven hours a day on screens, according to Ofcom’s latest report. That’s more time than they spend sleeping.

The research is pretty convincing. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) found that “students who read for pleasure perform significantly better in reading tests than those who do not, regardless of socio-economic background.” In other words, reading is not just a pastime that fewer and fewer of us engage in, it could actually be a predictor of success. And this success is not just limited to literacy. Studies show that regular readers develop stronger problem-solving skills, richer vocabularies, and greater empathy. Reading shapes not only what we know, but how we think and who we become.

And it starts early. A landmark study by Bus, Van IJzendoorn & Pellegrini (1995) concluded that “Parent-child reading is one of the strongest predictors of later achievement.” When we read aloud, we do more than share stories, we model curiosity, empathy, and the simple joy of words. We create a ritual that says: this matters. What’s more, you’re creating memories. I can still recall my father reading Winnie The Pooh out loud to me with all the voices, Eeyore being nasal and depressed, Pooh sounding as though he’d eaten too much, Piglet excitable and squeaky, Kanga Australian, Owl with a hooty voice and Rabbit being Welsh (a pun on Welsh rarebit!)

When we read aloud, we do more than share stories, we model curiosity, empathy, and the simple joy of words. We create a ritual that says: this matters. What’s more, you’re creating memories.

And if you are read to, you are more likely to go on and read for yourself. Clark and Rumbold (National Literacy Trust, 2006) remind us that “Reading for pleasure is more important for children’s cognitive development than their parents’ level of education.” That is a striking statement. It means that the habit of reading, voluntarily and joyfully, can outweigh even the most privileged starting points. It is not about having shelves of books; it is about choosing to open them.

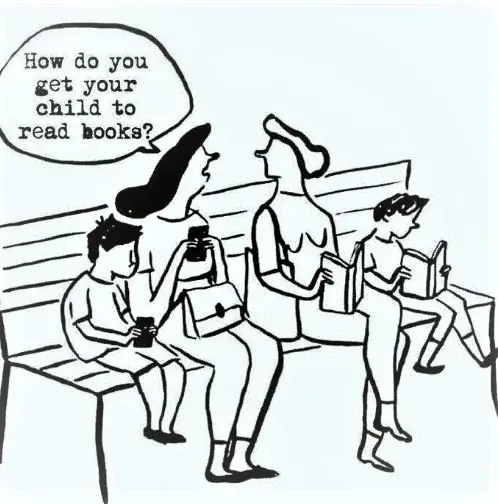

So where do we, as adults, fit in? Quite simply, we must lead by example. If young people see us scrolling endlessly, they learn that screens matter most. If they see us absorbed in a book, they learn that ideas matter most. Reading is caught as much as taught. I often say to parents: if you want your child to read, let them catch you reading. Let them see you laugh at a line, pause to think, or even shed a tear. Those moments speak louder than any lecture.

Of course, I am not suggesting we wage war on technology. Screens have their place. They connect us, inform us, entertain us. But they should not replace the deep, sustained engagement that reading demands. As Maryanne Wolf writes in Reader, Come Home (2018), “We are not only what we read, we are how we read.” And how we read, slowly and reflectively, shapes how we think. When we skim over things, we learn to skim over life. When we linger, we learn to linger over ideas, over people, over choices.

At Pocklington, we talk often about preparing young people not just for exams, but for life. Reading is one of the simplest, most profound ways to do that.

At Pocklington, we talk often about preparing young people not just for exams, but for life. Reading is one of the simplest, most profound ways to do that. Our Drop Everything And Read days support that, and we are keen to continue to develop those instances when we insist that everyone, and I mean everyone, sits down and reads a book. It builds vocabulary, yes, but importantly also imagination, empathy, and resilience. It teaches that clarifying meaning is not always instant, that some rewards require patience. In a world of instant gratification, that is a vital lesson.

So tonight, perhaps put your phone aside. Pick up a book. And if you have young people around you, let them see you do it. And if they ask why, tell them this: because stories make us human, and because in a world of constant noise, the quiet act of reading might just be the most courageous thing we can do.